Stela 14

Piedras Negras, Guatemala

On Display - Mexico and Central America Gallery

This historical hypothesis redirected the study of Maya writing as profoundly as had Förstemann’s. Suddenly solid bits of biographical information about the rulers could be derived from such features as the pose and costuming of their carved portraits.

Stela 14 was one of 40 limestone monuments that originally stood at the site of Piedras Negras, Guatemala. It shows a ruler sitting on a raised dais reached by a ladder. He wears an elaborate headdress, a heavy jade necklace and wristlets, and holds a bag containing incense. His name, elements of which are found in his headdress, was Yo’nal Ahk, and the inscription on the left side tells us that he came to power in 758 CE. To one side of the ladder, stands a woman holding a bundle of feathers who is almost certainly his mother. Her name once appeared on the right side of the monument, but unfortunately it is now too eroded to read.

This and other stelae from Piedras Negras played a key role in the decipherment of Maya history. Tatiana Proskouriakoff, an artist and researcher at Penn Museum in the 1930s, used them to make connections between particular hieroglyphs and the dates on which they occurred, realizing that one such sign referred to the birth of a ruler, another to his accession to power. Her groundbreaking article in 1960 overturned the long-held belief that Maya monuments were entirely religious in nature, demonstrating that they instead celebrated the lives of kings and their dynasties. Today scholars can read far more of the inscriptions—and can even pronounce them in their original language—but Proskouriakoff’s original insights have stood the test of time.

Expedition - Piedras Negras

Learn more about the Penn Museum’s excavation to Piedras Negras and the history behind the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. Travel back in time to meet J. Alden Mason, Linton Satterthwaite, and Tatiana Proskouriakoff and how they brought us closer to understanding the ancient Maya civilization.

The site of Piedras Negras sits among a group of hills that rise above the northern bank of the Usumacinta River, a fast-flowing waterway that today separates Guatemala from Mexico. A series of temples, plazas, ballcourts, and grand residences define the core of city, with the bulk of the population living in adjacent valleys and on surrounding hillsides. The Penn Museum conducted excavations there in the years 1931-1939, making a number of important discoveries, including new monuments and at least one royal burial. Thanks to this and subsequent research, we know that Piedras Negras was first occupied around 700 BCE. However, newcomers bringing new ideas and styles of governance arrived from the central Maya region around 300 CE. This marks the beginning of its dynastic history and we currently know the names of 11 kings who ruled between about 460 and 808 CE.

Piedras Negras had close contacts with its neighboring kingdoms, sometimes of a diplomatic nature—including royal marriages—but just as often was at war with them. Its main competitor lay to the east at Yaxchilan, another city built on the banks of the Usumacinta River. Recent fieldwork has shown that the land border between Yaxchilan and Piedras Negras was fortified with palisades and strongpoints that blocked movement through this hilly landscape. Conflict between the two kingdoms continued until the very end of their history, with the last inscription at Yaxchilan recording the capture of the last known Piedras Negras king in 808 CE. Very soon after both cities were abandoned as part of the wider collapse of Maya civilization in this region.

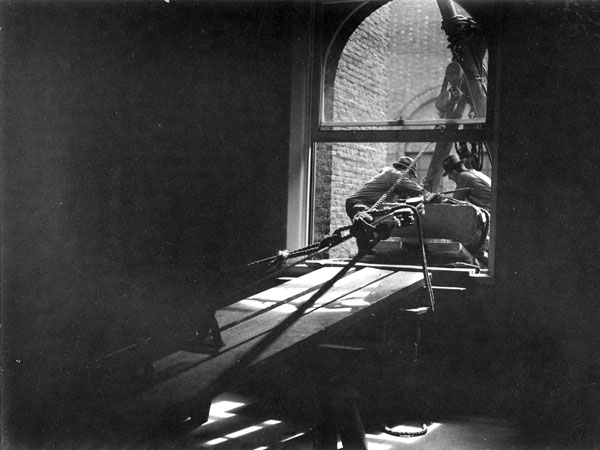

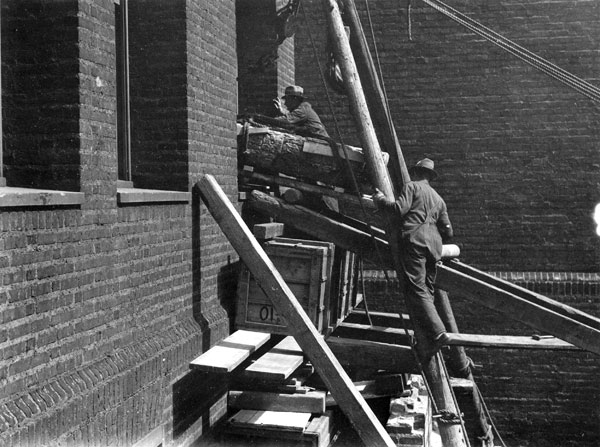

Stela 14 Entering the Penn Museum

Online Resources

Penn Museum Blog

Magazine Articles