During an initial site survey at Abydos in 1966, David O’Connor briefly examined South Abydos: a part of the site which had not seen substantial excavations since work from 1899–1904 by the British Egypt Exploration Fund. This area of Abydos includes the royal mortuary complexes of the 12th-Dynasty king Senwosret III (ca. 1850 BCE) and the 18th-Dynasty king Ahmose (ca. 1550 BCE), the founding pharaoh of Egypt’s New Kingdom. South Abydos remained highly promising for renewed archaeological work. O’Connor mapped and photographed the landscape at that time and even made trial excavations into deposits close to the pyramid of Ahmose.

Although O’Connor initially applied to the Egyptian Antiquities Service to excavate through the entire site of Abydos, he was only granted permission to dig at the area of North Abydos where he started work in 1967. Later, in the 1990s, separate permission was granted for new work at the Ahmose complex, initially excavated by Stephen Harvey from 1993–2007 as part of the Ahmose and Testisheri Project, and now under the aegis of the 30 Egyptian-American ASP project (see article by Vischak and Damarany on Page # of this issue). Excavations under my direction in the Senwosret III area were initiated in 1994 and continue to this day as the Penn Museum excavations at South Abydos. Over the last two decades, numerous discoveries have come from the broader environs of the Senwosret III mortuary complex including the 2013–14 discovery of the tomb of King Seneb-Kay discussed in this issue.

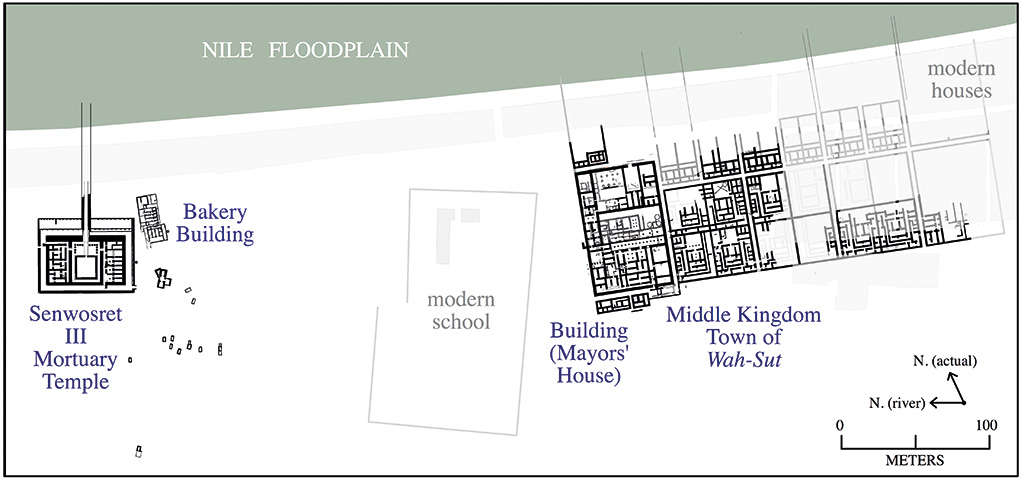

In the late 1990s, one of the noteworthy discoveries at South Abydos was the identification of the ancient town of Wah-Sut-Khakaure-maa-kheru-em-Abdju (usually shortened to Wah-Sut), which translates to “Enduring are the Places of Khakaure-justified-in Abydos.” This presence of a settlement site in this part of Abydos had been observed by earlier archaeologists including O’Connor. In 1902–03, working for the Egypt Exploration Fund, the Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly excavated two large houses in this area, which he attributed to the period of King Ahmose. In the 1990s, we discovered that this site was, in fact, the town of Wah-Sut, founded ca. 1850 BCE to house the community involved in maintaining the mortuary cult of Senwosret III. One of the first parts of the town identified was the mayoral residence, “Building A,” a complex of palatial dimensions (53 by 85 meters). Excavation of that structure, which spanned many seasons, was completed in 2015 and final publication of the results are in progress. Work in areas adjacent to the mayor’s residence revealed smaller scale houses arrayed in planned town blocks composing a substantial, state-planned urban center that had been built as a kind of satellite community or “suburb” to the main town of Abydos.

Small objects from the town excavations 2022–23: a duck amulet (upper left), ivory inlay with a baboon (upper right), a scarab (lower right), and miniature statuette of a man (lower left); photos by Ayman Damarany.

In recent seasons, we have been engaged in expanding the excavations of the Wah-Sut town site with the goal of exhaustively excavating the preserved and accessible areas of the ancient town. One of our primary areas of interest is the ways in which the town adapted to and made use of its environmental setting at the edge of the Nile floodplain. In ancient times, one of the perennial concerns of inhabitants of the Nile Valley was the reach of the waters of the annual Nile inundation, which reliably flooded the cultivated landscape flanking the river every year between June and September. The Nile flood, called Hapy by the Egyptians and envisioned as a god of fertility, was a benefit to Egypt’s riverine ecosystem and formed the basis of agriculture in Egypt by continual replenishment of the iron-rich alluvium. However, the flood was also a logistical concern for the Egyptians. Because they built their domestic and urban sites primarily from mudbrick dug from the floodplain itself, habitation sites needed to be situated on parts of the landscape that lay above the normal reach of the flood waters. In some parts of Egypt, high mounds developed along old river levees gradually building into huge settlement mounds called tells or koms (such as the Kom es-Sultan at North Abydos). In many areas of the Nile Valley, the edge of the desert was an inviting location for situating settlements. Wah-Sut is one such settlement.

2022–23 Excavations

With support from the Penn Museum’s Director’s Field Fund, the generous support of E. Jean Walker and Nina Robinson Vitow, and crucial grant support from the American Research Center in Egypt, during our 2021–2023 seasons we completed large exposures inside the town of Wah-Sut, as well as test units in areas between the modern buildings aimed at investigating the extent of urban remains and studying the town’s relationship with its wider landscape. To the local south of the mayoral residence (Building A) are a series of additional large residences arranged in blocks of four contiguous houses (Buildings B though M). The blocks are separated by access streets forming a planned urban layout. It was two of these that Charles Currelly first exposed in 1902–03, mistakenly dating their initial construction to the New Kingdom (we now know they belong to the Middle Kingdom). Although the houses excavated by Currelly are now mostly covered by modern buildings, others of similar design are accessible and have been a priority for excavation.

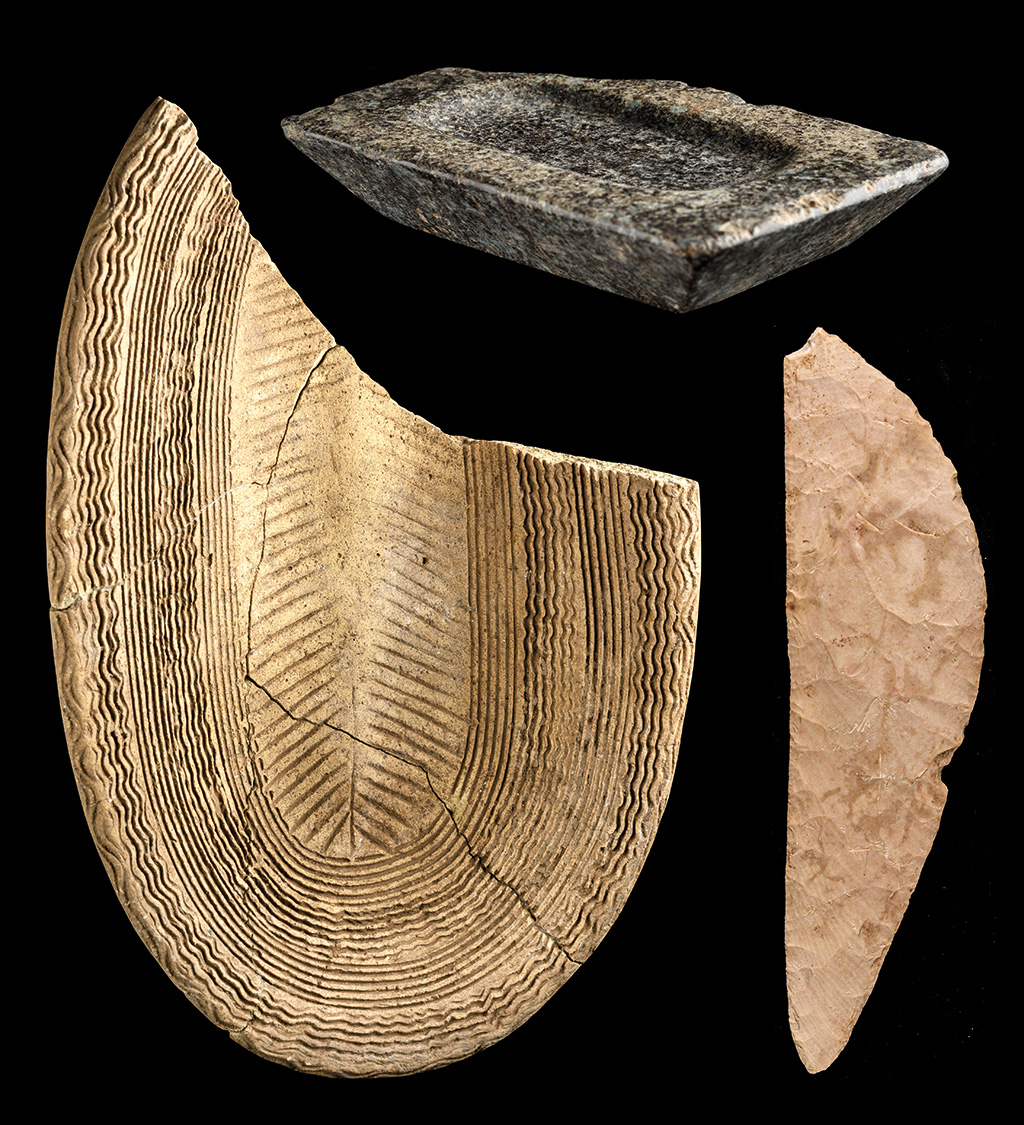

During the summer of 2022, a large exposure revealed something that we had long sought evidence for at Wah-Sut: smaller scale houses. It has long been clear that the southern and higher elevated side of the town was dominated by the large, elite residences. We theorized that smaller houses should compose the bulk of the town and were likely located on the lower-elevated parts of the landscape directly abutting the floodplain where primary agricultural activities occurred. Indeed, one surviving late Middle Kingdom papyrus that mentions our town refers to the “fields and orchards of Wah-Sut,” Objects of crafts and industry Discovered in 2023 at Wah-Sut: a granite palette (top), a husking tray (left), and a flint knife (right), photos by Ayman Damarany. and from 2016–2020 we excavated a bakery and brewery complex close to the temple of Senwosret III that indicates extensive food production activities along the floodplain flanking Wah-Sut. To the north of the blocks of elite residences, we found that the housing blocks are half as wide and divided into houses one quarter the area of the larger ones.

Discovered in 2023 at Wah-Sut: a granite palette (top), a husking tray (left), and a flint knife (right), photos by Ayman Damarany.

This crucial sector of the town is still under investigation, and we hope to be able to trace remains down the sloping edge of the low desert into the area now covered by the modern floodplain. Over the last four millennia, through the deposition of silt, the inundation has incrementally raised the alluvium, thereby pushing the Nile floodplain outwards and upwards burying areas of the low desert that once lay beyond the reach of the flood. Preservation in and adjacent to the floodplain is much more limited than what survives at higher elevation on the desert edge. Although much of this lower status housing along the edge of the cultivation is probably destroyed, we hope to gain crucial evidence through future work to trace the full extent of the town and see how it related to its floodplain surroundings.

As part of the program to fully document the still accessible areas of Wah-Sut, during the 2023 season, we completed the exposure of two of the large houses— Buildings F and H—that lie to the south of the mayoral residence. Excavating in 10-by-10 meter squares, and gradually expanding our exposure over two months, we witnessed the structure of an ancient Egyptian neighborhood emerge. Carefully designed houses that had been formed by an architect’s blueprint had been lived in by generations of people spanning several centuries and changed in ways to suit their needs. In some areas we found doors were blocked up, and staircases added or removed. Although the town’s ruins have been severely impacted over the last four millennia, the surviving architecture and deposits provide crucial evidence on the way these households were used by ancient Egyptians. A wide variety of artifacts—from objects of adornment to tools used in domestic production and industry—reflect the long-ago life of Wah-Sut.

The People of Wah-Sut

Two fragments of Middle Kingdom stelae discovered in 2023. The text on the stela at the top records a man who was a “phyle director of King Khakaure.” The lower shows men (above) and women holding lotuses (below), one of whom is the “Lady of the house, Renseneb”; photo by Ayman Damarany.

As we continue to excavate and work toward reconstructing this ancient town and the life of its inhabitants, a welcome source of information are artifacts that records the identity of the people who once lived here. In past seasons, this crucial evidence has come in the form of clay sealings impressed by means of scarab and stamp seals. Seals were sometimes inscribed with hieroglyphic texts that record the names and titles of people who lived and worked at Wah-Sut. On this basis we have been able to recover the identity of many of the mayors who once administered Wah-Sut and reconstruct a local mayoral history for the community between ca. 1850 and 1650 BCE. Many other members of the community are also recorded on seals.

Another source, though in many ways still a mysterious one, are fragments of inscribed objects—stelae, statuettes, and offering tables—that we find scattered inside and around the ancient buildings. Although these often record the names and titles of Wah-Sut’s inhabitants, it is not clear if these fragments originated from domestic shrines where people commemorated and made offerings to their deceased family members, or if some of these have been displaced from nearby chapels or shrines that lay in the town’s wider vicinity. Although many thousands of people clearly lived and died at Wah-Sut over its centuries-long history, we have yet to conclusively identify the location of the private cemeteries linked with Wah-Sut. Some of the inscribed objects suggest they may originate from ancient cemeteries in the vicinity. It is immensely rewarding to see the names and faces of these ancient people as they recorded themselves on these artifacts of commemoration. Excavations planned for coming years aim to further probe the desert and floodplain surroundings of the Wah-Sut town site to help us further understand the way this community lived and evolved over several centuries, and how this state-planned “suburb” of Abydos might have adapted to major social and political changes that occurred in Egypt’s late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period.